Over the years, Te Pihopatanga o Aotearoa has made a point of reaching out to indigenous Anglicans in other parts of the world.

It learned just how much fruit those efforts have borne at its biennial runanganui, which wrapped up in Auckland yesterday.

Four years ago, at its 2005 gathering in Otaki, Te Runanganui had hosted two indigenous Canadian guests.

The delegates at Otaki heard a story they could identify with – of Anglicans yearning to worship in their own ways, and yearning for bishops of their own kind. Those Canadians had shared how they’d been making representations to the Anglican Church in Canada for years – and been told how it might be possible to have their own indigenous bishop by 2013.

Well, that timetable got turbocharged.

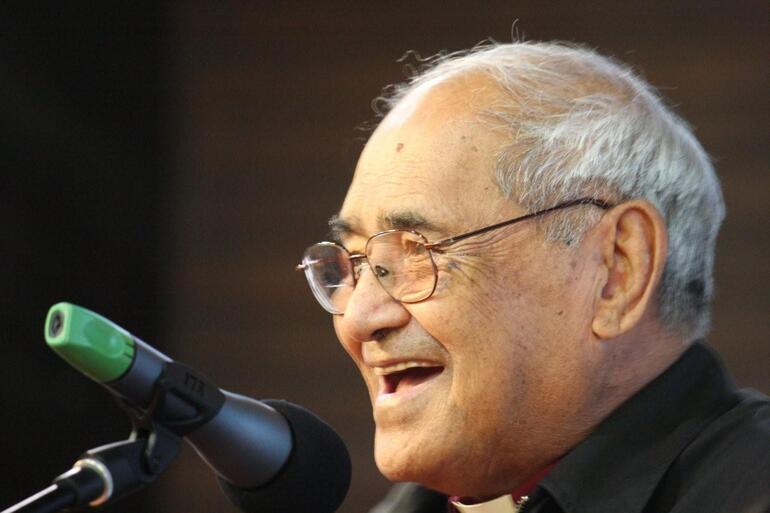

Because on Friday, Te Runanganui heard from The Right Reverent Mark Macdonald, who is Canada’s first National Indigenous Bishop.

He was elected to that new post in January 2007 – and last Friday he painted a picture of an indigenous church that is racing towards full autonomy, as a sub-province within the Anglican Church of Canada.

In five major tribal regions of the country they’re moving toward separate church jurisdictions, and by the next northern summer Bishop MacDonald expects a further two or three indigenous bishops in place.

He paid tribute to the Pihopatanga for setting the example of what is possible: “Your church,” he told the delegates, “has inspired and instructed us.”

He said visits to Canada by Maori Anglicans, and Maori input into the Anglican Indigenous Network, “had articulated so many things that we had wanted, but not known how to speak about.”

“We had not thought about the way our treaties affected us as a church. Our lives were in boxes, and the church box had nothing to do with treaty box.”

Bishop Macdonald said that when he was chosen as Canada’s National Indigenous Bishop, he expected to spend 10 years “rolling a boulder up a hill”, explaining to sceptics why an indigenous Anglican church was needed.

Instead, he said, he’d found that God had already rolled that boulder to the summit – “and I’ve been chasing it downhill ever since.”

The Pihopatanga’s encouragement of indigenous people hasn’t been limited to its Canadian outreach, either: because two of the guests at this year’s runanganui were indigenous Hawaiians.

Mrs Sandy Padeken and Keane Akao spoke of their own Diocese of Hawaii – which has just one native Hawaiian clergy person, who will retire next year – and of the encouragement they’d taken from being in the midst of a thriving gathering of Maori Anglicans. Ms Shannon Smith, from New South Wales, also spoke on behalf of the Australian Anglican Indigenous Network.

Meanwhile, there were significant contributions from the Sydney Maori Mission – Archdeacon Malcolm Karipa led a delegation of 12 from Te Wairau Tapu, the Anglican Church in Redfern, to Te Runanganui – while there were five folk on hand from the Brisbane Maori Mission.

Other highlights from Te Runanganui included:

An airing of the history and issues swirling around the debate about the ordination of gay and lesbian people. Bishop Kito Pikaahu introduced that session, and spoke of a sense of the Pihopatanga being pressured to reach a decision about where it stands.

Bishop Victoria Matthews, from the Diocese of Christchurch then traversed the history of the issue in the Anglican Communion, and the communion’s efforts to resolve it. One of the questions raised, she says, is: “What does holiness and humility look like today?”

Then there was a political forum, at which The Minister of Maori Affairs, Dr Pita Sharples, and former Labour cabinet ministers Parekura Horomia and Shane Jones shared their own stories – and also spoke of their struggles with a bureaucracy that, where Maori aspirations are concerned, is often uncomprehending, and hard to budge.

The three MPs made it clear that the bonds of whanaungatanga, and their desire to make things better for iwi Maori, go deeper than political rivalry.

The future of the Anglican Maori boarding schools remains a hot button issue. Both the surviving schools, Te Aute and Hukarere Colleges, are struggling with small rolls and dwindling income. Te Runanganui heard an outline of proposals for a new governance structure for both those schools – and it reserved its judgement on that. It passed a motion inviting the Te Aute Trust Board “to urgently supply the detail” of that governance structure to the next meeting of Te Runanga Whaiti, the standing committee of Te Pihopatanga.

They also heard of Hukarere’s fundraising project to re-open Te Manawa o Hukarere, a new school chapel. When the school moved from Bluff Hill in Napier to Eskdale 10 years ago, the old school chapel was demolished, and its taonga and pews were put into storage, where they’ve remained ever since.

And the chairperson of the St Stephens and Queen Victoria School Trust Boards, John Fairbrother, spoke of his board’s determination to build an investment base that’s strong enough to sustain any future developments – whether that be to re-establish those schools themselves, or to provide education by some other means, for example via a scholarship programme.

He also spoke of the new board’s determination to build relationships with the old boys and old girls from the two defunct schools, and to hone the skills of the Trust Board members.

The next issue of Taonga magazine will carry a full report on Te Runanganui.

Comments

Log in or create a user account to comment.