Social Investment

What we support

Church leaders support the concept of Social Investment as a way of building the wellbeing of New Zealanders.

While there are several different definitions of Social Investment, the one provided by Dorothy Adams at her Treasury Guest Lecture on March 22nd 2017 resonates most strongly:

“Getting the right help to people who need it, at the time it will make the most difference – At a time of most benefit to the people who need it.”

This is an expression of Social Investment which best describes an approach focussed on the wellbeing of family, whanau and community (as opposed to the fiscal model that appeared to be the driver of earlier iterations) and is thus more likely to lead to a wider range of supports and interventions.

Who we are

Faith-based social services have a long and deep engagement with people who need help to thrive.

Within the New Zealand Council of Christian Social Services membership network there are 213 different community-based social service centres, providing 37 different types of services via 1,024 programmes.

Service centres are in 55 towns and cities throughout New Zealand. They deliver $671mil in services each year, $426mil funded by government, $16mil funded by philanthropy and $228mil from their own funding sources. This does not include the many church-based community social work, chaplaincy and community development initiatives offered directly from local congregations.

Our experience of the social investment approach

The initial social investment data presented a picture that said much of the social service sector was not making much difference to those most trapped in negative life-cycles.

We think this has some truth to it. The problem is that the reasons why the system is failing this group have not been deeply explored. The current focus on the investment approach appears to be intensifying past approaches through implementing a more targeted approach.

We have seen government agencies working towards a particular perspective on Social Investment.

These agencies appear to be focused on:

• Tightly targeting interventions at individual level

• Redistribution of existing service support funding rather than investing new funding

• Developing an actuarial model of intervention rather than a wellbeing approach

This has led to the impression of an ever-more tightly focussed range of interventions based on predictive risk modelling data that will potentially allow for the measurement of an actuarial “return on investment”.

This approach drives tight targeting of those for whom measurement of return may be achieved through linking administrative data to provide predictive risk modelling and potential costs savings.

It also appears to be behind the current, controversial push by MSD for the collection and sharing of Individual Client Level Data.

Our members cite a range of client needs that contribute to high vulnerability, putting them and their families on a pathway to poor outcomes.

These people may present with housing issues, inadequate and insecure employment, high levels of debt, family breakdown and stress, children with undiagnosed learning or health issues, parenting issues and resulting problem child behaviours, unreported child abuse or family violence, addictions and untreated poor mental health.

Many of our clients report that they feel isolated and disconnected to their community.

Combinations of these issues lead to high levels of vulnerability that will eventually lead many to become part of the administrative data statistics and predictive risk model targeting, however they often remain hidden from this administrative data until then.

In some cases, this may be too late as the stresses on the families may mean they are no longer able to respond favourably to the services being offered – they are no longer ‘ready for change’.

Our concerns

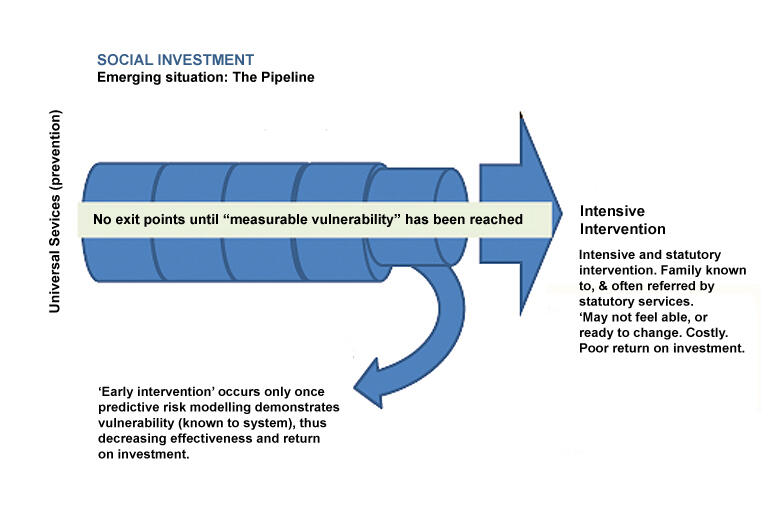

The targeted approach is leading to an unintended consequence of developing a ‘pipeline’* to extreme vulnerability and more intensive intervention.

Without the voluntary interventions available from community based providers, families will need to wait until they can be ‘diagnosed’ as ‘extremely vulnerable’ within very narrow parameters and able to produce a “measurable return on investment” before they can access the services they need.

This is usually when families or individuals interface with statutory services and are ‘knowable’ to linked administrative datasets.

*See the ‘pipeline’ model detailed in image 1, above

Emerging situation

The approach taken by officials is leading us more towards a situation where vulnerability must be ‘proved’ to allow for targeting before interventions occur.

Our preferred approach

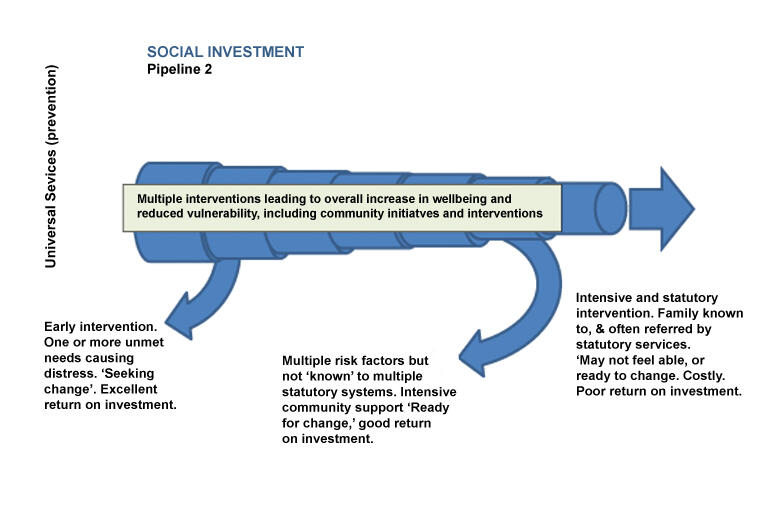

The experience of Christian social services is that the best return is achieved when the individual/family/whanau is ready for change, and when they make a positive connection with both community organisations and practitioners delivering interventions.

This may be after several of the targeted predictive risk factors have been reached and the diversion of the family to a new path may be measurable over time.

Or it may be before vulnerability linked to administrative data has occurred, however, the family is vulnerable, recognises this and seeks help through known place-based organisations, although may not be clear about what services will best meet their need.

These interventions may produce the best “return on investment’ in that it may be able, with little resource input, to increase skills, resilience and natural support systems to keep the whanau at a sustainable level of wellbeing without further government intervention.

However, the tight targeting approach means that less and less of this highly effective level of work is occurring. The inability of government agencies to use information NGOs collect and report to funders in addition to their contracted reporting measures, has ensured that the effectiveness of this work has remained hidden from government’s view.

The second model (Image 2, above) is closer to present delivery models, and could result in a “refined approach” taking the best of current models and experience and refining them through the application of a well-being focussed Social Investment system.

Our offer to support change

Church leaders recognise that both the churches and government want to address the issues that lead people to become vulnerable and to support already vulnerable people towards independence.

This will require identifying how we can get the right help to the people who need it, when they need it and they are ready for change – so that it makes the best possible difference.

It also means we will need coordinated systems to understand who the people who need help are, and how effective the help provided is in supporting individual/family/whanau/community wellbeing.

Church leaders are very interested in working with government in more deeply exploring the issues associated with using social services to make a bigger differences in the lives of the families/whanau in our communities.

We want to be involved in the further development of the Social Investment system towards a wellbeing-based model and seek ways at engaging at influential levels in the process of this development.

Comments

Log in or create a user account to comment.